Uncovering the Performative Gap: How Workplace Stress Pushes Us from Problem Solvers to Protectors

Abstract

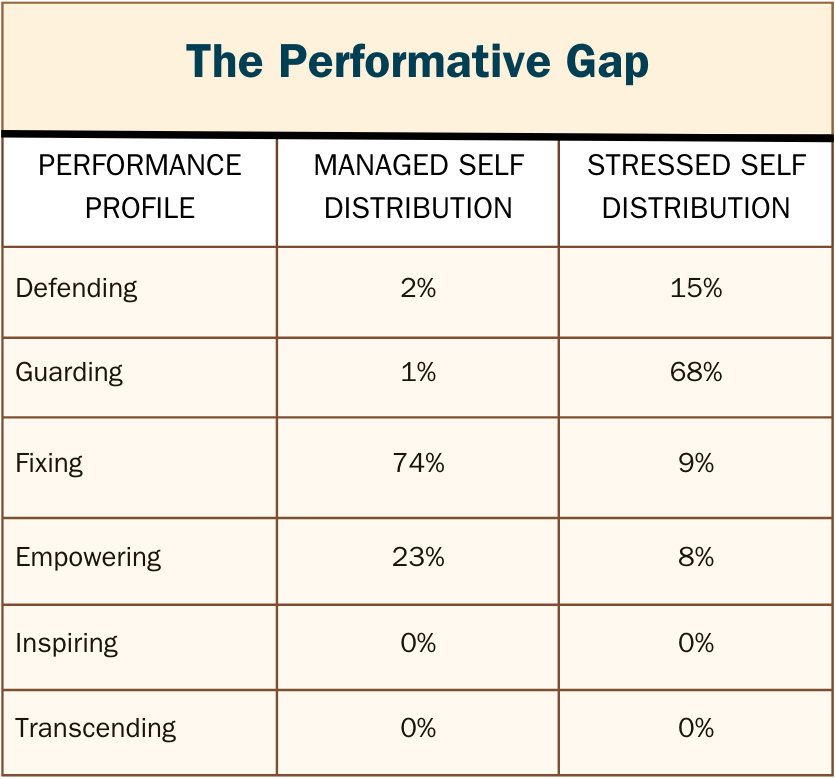

When stress and conflict enter the workplace, most professionals experience a dramatic shift in how they operate. A study of 223 participants using the Emotional Intelligence 3.0 Power Style Indicator reveals a distinct performative gap: the measurable difference between how people perform in stable conditions (managed self) and how they respond under stress (stressed self). While 74% of respondents adopt a solution-focused Fixing profile in calm conditions, this drops to just 9% under stress. Most shift to protective stances. This research explores how stress triggers three predictable defensive strategies—withdrawal, dominance, and over-helping—each rooted in false beliefs about safety. By understanding this performative gap, individuals and organizations can begin to close it, creating cultures where people maintain their collaborative capacity, problem-solving ability, and growth orientation even during conflict and change.

Keywords

Power, Influence, Choice, Drama, Conflict, Collaboration, Organizational Performance, Drama Triangle

Table of Contents Show

Introduction: The Two Faces of Workplace Performance

Think about yourself at work. Are you the same person in calm moments as you are when tension rises? Most of us aren't. When stress enters the room, something shifts. We move from our best selves to survival mode.

This gap isn't a character flaw. It's neurological. When our brains perceive threat, emotional safety becomes paramount. We unconsciously activate a defensive posture through emotional safety strategies. These strategies are designed to protect us. The problem: these same strategies that keep us safe often undermine collaboration and resolution of challenges.

A recent study of 223 employees in the same organization reveals this hidden dynamic in striking detail. The data shows a clear performative gap: the measurable difference between how people operate when calm (their managed self) and how they respond under stress (their stressed self). See figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Power Style Inventory

The Power Style Inventory was used to collect data. It provides insights into how stress influences your Collaboration Style by measuring the difference between how people perform in stable conditions (managed self) and how they respond under stress (stressed self).

Collaboration epitomizes how a person chooses to belong in any situation, making choice crucial to a person’s way of being in the world. The right to choose is an individual’s point of personal power.

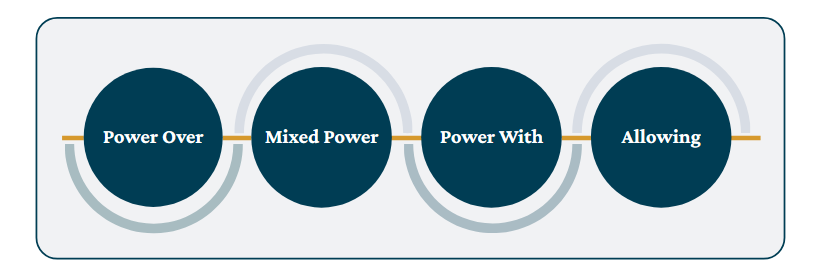

Power unfolds along an organic development path, becoming increasingly collaborative at each phase. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Collaboration Style Descriptions

Here is an expanation of each Collaboration Style

Power Over

• Exercising authority protectively to control outcomes and people, often by withdrawing, over-helping, displaying incivility, or using antagonism to assert dominance and limit conversation.

• Tends to exercise control reactively, based on immediate personal perspective and limited awareness of how decisions affect broader relationship dynamics and stakeholder needs.

• Prioritizes individual interests and personal wins over collective goals, with difficulty momentarily detaching from personal viewpoints during conflicts.

• May attempt to consider broader or collective goals, but often reverts to self-interest when stakes feel high or when maintaining control seems necessary.

• Patterns of control that perpetuate destructive conflict, though with growing (yet limited) awareness of how these approaches constrain outcomes and relationships.

Mixed Power

• Alternating between control and partnership, sometimes shifting from asserting authority to sharing influence, reflecting tension between dominance and mutuality.

• Beginning to recognize how power impacts others; actively struggles to balance personal power and control with empowering others' voices and perspectives.

• Sometimes able to separate personal perspectives from broader stakeholder needs and organizational objectives, especially in lower-intensity situations.

• Inconsistently attempts to consider the needs and goals of others, the team, and the organization, though often reverts to control-oriented approaches during conflicts or when feeling threatened.

• Patterns gradually evolving toward more constructive engagement, where differing perspectives are sometimes seen as valuable rather than threatening, though this shift remains fragile and situational.

Power With

• Sharing influence through open, respectful dialogue that prioritizes co-creation and understanding, allowing everyone to contribute and help shape the outcome.

• Consistently and proactively uses power to advance collective goals while maintaining individual integrity, skillfully balancing others' needs and interests with personal considerations.

• Consistently prioritizes broader objectives and shared goals over personal considerations during conflicts and complex decisions.

• Generally fosters a positive and open environment for sharing ideas and diverse perspectives, though may not always maximize group creativity or engagement.

• Exhibits patterns that generate constructive conflict, where disagreement and diverse viewpoints are leveraged to strengthen relationships and outcomes while maintaining focus on shared goals.

• Demonstrates growing ability to see the broader needs and objectives of all stakeholders and facilitates collaborative problem-solving and innovation.

Allowing

• Jointly generating creative solutions by balancing influence among participants, integrating diverse perspectives, so that new possibilities emerge through the collective.

• Uses power to amplify others' voices and create conditions where others feel confident taking initiative and making meaningful contributions.

• Expertly creates space for others' creativity and perspectives to emerge and drive outcomes, seeing the broader needs and objectives of all stakeholders.

• Patterns of allowing that transform potential conflict into creative partnership and mutual empowerment, leveraging disagreement and diverse perspectives to strengthen relationships and generate innovative solutions.

• Leverages timeless values of openness, curiosity, and respect for all perspectives; actively creates a safe and open space for authentic communication and collaboration with all stakeholders and systems.

• These collaborative patterns create a consistently generative environment where conflict becomes a valued catalyst for innovation and collective breakthrough .

The Six Profiles

The EI3.0 Emotional Evolution Framework uses six performance profiles for the managed self and the stressed self: Defending, Guarding, Fixing, Empowering, Inspiring, and Transcending. While the profile names are the same, the patterns are different.

It is essential to appreciate that Profiles are neither good nor bad. They are just a location on the map of emotional evolution. Every profile has positives and negatives.

Here are the descriptions of the six Managed Self Profiles:

Defending - Managed Self

• Typically perceived as self-protective and distant.

• Others often experience them as resistant to close engagement, quick to challenge perceived threats or withdraw, and difficult to build deep connections with.

• Their defensive posture can create formidable relationship barriers.

Guarding - Managed Self

• Often perceived as cautious and reserved, maintaining a heightened awareness of group dynamics.

• Others may experience them as someone who holds back, carefully measuring situations for perceived danger before acting, or may be seen as passive.

• Their protective stance can create significant distance in relationships.

Fixing - Managed Self

• Appears as a practical problem-solver who brings structure and clarity to situations.

• Others experience them as competent and solution-focused, with a natural ability to identify and implement improvements while maintaining supportive relationships. May overstep in their need to fix (disrupts connection and collaboration).

Empowering - Managed Self

• Appears as a steady, capable presence who naturally builds supportive environments where others can thrive.

• People experience them as someone who consistently demonstrates competence while encouraging mutual respect and shared achievement.

Inspiring - Managed Self

• Shows up as a natural catalyst for positive change, expertly bringing people together around shared visions.

• Others experience them as a confident yet approachable person who creates meaningful connections and inspires collaborative growth through their genuine enthusiasm and emotional balance.

Transcending - Managed Self

• Presents as a deeply grounded individual who embodies profound self-awareness and natural wisdom.

• Others experience them as authentically present, creating spaces where transformation seems inevitable rather than forced.

• Their integration of personal wisdom manifests as a quiet authority that naturally elevates conversations and relationships.

Here are the descriptions of the six Stressed Self Profiles:

Defending - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation destabilizes rapidly with increasing stress. Behaviors become rigid and self-protective.

• A person experiences distorted self-worth and self-authority.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "The world is threatening, so I must protect myself from harm."

• Low emotional balance that entangles.

Guarding - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation becomes increasingly unstable as stress levels rise. Behaviors focus on creating personal safety through control and distance.

• A recognition of self-worth and personal authority emerges, but self-perceptions remain distorted.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "It's not a safe world, so I have to be hyper-alert to avoid potential dangers."

• Low emotional balance that entangles.

Fixing - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation is conditionally stable and requires external validation. Under stress, behaviors fluctuate between self-assertion, avoidance, and accommodation.

• A person develops a sense of self-worth and begins exercising personal authority, but self-perceptions remain distorted.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "Let's all just get along."

• Developing emotional balance but still entangles more than not.

Empowering - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation is confidently established, supporting self and others. Behaviors are consistently self-directed and supportive of others under stress.

• A person has a strong sense of self-worth and confidently exercises their personal authority.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "I am empowered to author my own life and take responsibility for my choices."

• Advancing emotional balance, a person engages more often than not. Behaviors become more consistent in times of low and high stress.

Inspiring - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation is highly stable, enabling positive influence on others. Behaviors are consistently growth-oriented, even under stress.

• A person has fully embraced their worth and authority.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "I partner with the system of life to create things that make a difference."

• Emotional balance is achieved, and a person fully engages.

Transcending - Stressed Self

• Emotional regulation is highly stable, allowing for deep expressions of the authentic self. Behaviors are consistently aligned with timeless values regardless of stress levels.

• A person fully accepts and embodies their physical, mental, and emotional design.

• Based on a set of beliefs best summarized as "I am interconnected with all of existence and act from a place of universal wisdom, love, and power."

• System balance that fully engages with self, others, life, and the system.

Power, Choice, and the Drama Triangle

Power often gets a bad name in workplaces. We think of it as dominance, control, and winning at others' expense. But authentic power is something different. It's the capacity to create from your unique strengths while contributing meaningfully to the larger whole— power with rather than power over.

When we feel unsafe, we rarely access power with. Instead, we activate one of three defensive strategies—each a variation on control through emotional safety:

Making ourselves small: "If I become helpless and powerless, I won't be attacked." This leads to withdrawal, resignation, and avoidance—the victim role in conflict.

Making ourselves bigger: "If I'm stronger and more powerful than everyone else, they can't hurt me." This manifests as blame, competition, dominance, and aggression—the persecutor role.

Making ourselves useful: "If I control things through helping, I'm valuable without claiming my own worth." This shows up as over-responsibility, excessive caretaking, and placating—the rescuer role.

These three roles form what Stephen Karpman called the Drama Triangle. Each offers a false sense of safety while perpetuating conflict. And when stressed, most of us gravitate toward one. Again, playing a role is neither good nor bad. It’s just something we do.

What the Data Reveals

What we saw from the participants is that stress due to conflict provokes self-protective measures:

In calm conditions, 23% adopt Empowering (builds supportive environments); 74% adopt Fixing (solution-focused), 1% adopt Guarding (protective), and 2% adopt Defending (rigid protection).

Under stress, 67% shift to Guarding, 13% shift to Defending, 9% retain problem-solving capacity with Fixing, and only 8% maintain the ability to focus outward to build a supportive environment as Empowering.

See Figure 1.

The ability to support others and problem-solve takes a massive hit under stress.

Notably absent in both conditions are the higher-performing profiles that represent growth-oriented, emotionally stable, and wisdom-driven behavior. Why? Because most organizational environments don't support or allow them to consistently emerge.

The performative gap tells us something fundamental to organizational performance: Projects, teams, and transformations don't fail because individuals lack capability. They fail because the stress that accompanies conflict, uncertainty, and change triggers predictable shifts toward self-protection. When 80% of problem-solvers become defensive, collaboration breaks down. Communication becomes self-protective. Innovation stalls. Conflicts escalate rather than resolve.

The performative gap is real, measurable, and costly. But it's not immutable.

The Path Forward

The good news: understanding your performative gap is the first step toward closing it. When you recognize how you typically respond under stress—where you default, what triggers you, which safety strategy you favor—you create choice. And choice is personal power.

But individual awareness isn't enough. Organizations must shift their culture and leadership practices to create environments where people can remain collaborative, innovative, and growth-oriented even in difficult times. This requires intentional design—in how we communicate, resolve conflict, distribute power, and hold space for vulnerability.

Imagine workplaces where stress doesn't automatically push people into a defensive posture. Where professionals can problem-solve, inspire, and grow—even in conflict. Where power is experienced as belonging and contribution rather than protection and control. This isn't idealistic. It's organizational design.

The performative gap exists in every organization. The question isn't whether it's there—it's what you'll do with the knowledge. Understanding how stress reshapes performance is the beginning of building teams and cultures that bring out our best selves, not just our protective selves.